Indian River Lagoon Estuary

Indian River Lagoon National Estuary spans 181 miles across Florida's East Coast, from Volusia's Halifax River southward to Jupiter Inlet in Palm Beach. The Indian River Lagoon estuary ranges through six Florida counties: Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach.

The Indian River Lagoon watershed includes four brackish water lagoons, five freshwater rivers, five ocean inlets, three National Wildlife Refuges and a National Seashore.

Indian River Lagoon National Estuary is known as "the most bio-diverse habitat in North America" due to the ecosystem's temperate location, varied habitat, and 4,000 plant and animal species.

The estuary's forests, wetlands, seagrass, spoil islands, shorelines and brackish water provide habitat suitable for terrestrial and marine species found in both fresh and salt water areas. Indian River Lagoon was designated as an "Estuary of National Significance" by the EPA's National Estuary Program in 1990. From 1991 to 2015, the St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) served as the host agency for the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program (IRLNEP). Today, the IRLNEP is locally managed by the Indian River Lagoon Council, an independent district of the State of Florida.

Geography

Moved only by wind and a minor tidal influence, the estuary's brackish lagoons are .5 to 5 miles wide and average only 4ft in depth.

The original 156 mile long Indian River Lagoon National Estuary covered 2,284 square miles, with a surface water area of 353 square miles.[1]

At the request of the Volusia County Council (Resolution 2015-133) and with support from the IRL Council (Resolution 2015-04), the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program (IRLNEP) adopted an Indian River Lagoon - Halifax River boundary amendment. After consideration by the IRLNEP Management Conference, the amendment was accepted by the IRL Council on November 18, 2016. The boundary revision extended the IRLNEP boundary northward 25 miles into the Volusia's Halifax River and added 198,678 acres to the estuary's watershed.[2] See Also: Geological_History

Watershed

The Indian River Lagoon National Estuary watershed comprises a bar-built estuary that merges five freshwater rivers (Tomoka, Eau Gallie, St. Sebastian, St. Lucie and Loxahatchee) and five saltwater inlets (Ponce de Leon, Sebastian, Ft. Pierce, St. Lucie and Jupiter) into four brackish water basins, Halifax River, Mosquito, Banana River, and Indian River lagoons.

Halifax River

The northern boundary of the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary is at Bulow Creek on the Halifax River in north Volusia County. Halifax River ranges southward to Ponce Inlet and Mosquito Lagoon.

- Bulow Creek

- Tomoka River

- Fozzard Creek

- Wilbur Bay

- Rose Bay

- Mill Creek

- Spruce Creek

- Braddock Creek

- Hunter Creek

- Callalisa Creek

- Elwinder Creek

- Bottle Island Creek

Mosquito Lagoon

Mosquito Lagoon spans 28 miles southward to Brevard County, where it connects the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) to the Indian River lagoon via Haulover Canal.

An outdoor lover's paradise, Mosquito Lagoon is bounded on the west by Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge (MINWR), on the east by Canaveral National Seashore, and on the south by Kennedy Space Center.

Banana River Lagoon

The Banana River lagoon begins at Banana Creek, near Titusville, spans southward thru Kennedy Space Center (KSC), to merge with the Indian River lagoon at Dragon's Point, the southernmost tip of Merritt Island. Northern Banana River lagoon lies within KSC property and is closed to the public.

Port Canaveral, at Banana River lagoon's mid-point, is major cruise, cargo and naval port. It is one of the busiest passenger ship terminals in the world and home to the Trident Submarine Base.

Port Canaveral provides minor saltwater inflow into Banana River when the Canaveral Lock is opened. The lock allows sea-going vessels to access the Banana River (KSC deliveries), or continue westward to cross Merritt Island in the Canaveral Barge Canal, and enter Indian River's Intracoastal Waterway.

Brevard

- Banana Creek

- Canaveral Lock

- Canaveral Barge Canal

- Sykes Creek

- Grand Canal

- Indian River

Indian River Lagoon

From it's northern boundary at Turnbull Creek in Brevard's Scottsmoor, Indian River lagoon extends 121 miles southward thru five Florida counties, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin and Palm Beach. Indian River receives saltwater from Sebastian, St. Lucie, Fort Pierce, and Jupiter inlets and receives freshwater from Eau Gallie, Sebastian, St. Lucie, and Loxahatchee Rivers. Lake Okeechobee connects to the Indian River in St. Lucie County, via the Okeechobee Waterway and the St. Lucie River.

The southern boundary of the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary is at Martin County's Sewall's Point, where the Loxahatchee River and Indian River meet Palm Beach County's Jupiter Inlet.

Brevard County

- Turnbull Creek

- Haulover Canal

- Gator Creek

- Catfish Creek

- Banana Creek

- Canaveral Barge Canal

- Horse Creek

- Banana River

- Eau Gallie River

- Crane Creek

- Turkey Creek

- Goat Creek

- Kid Creek

- Trout Creek

- Mullet Creek

Indian River County

- Saint Sebastian River

- Sebastian Inlet

St. Lucie County

- Taylor Creek

- Fort Pierce Inlet

- Moores Creek

Martin County

- Saint Lucie River

- Saint Lucie Inlet

Palm Beach County

- Loxahatchee River

- Jupiter Inlet

Biota

Home to more than 2,100 plants and 2,200 animal species, the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary is the most bio-diverse habitat in North America.[1]

The estuary contains many diverse natural habitats, from seagrass flats and mangrove shorelines to upland forests, that accommodate a vast array of plant and animal species. The estuary's saltwater inlets and freshwater tributaries blend together to form brackish water, which provides a unique habitat where plants and animals from both salt and freshwater habitats can reside.

Some species, including the Southeastern beach mouse, Atlantic salt marsh snake and Johnson's Seagrass are found nowhere else on earth. The Indian River Lagoon estuary is home to over 50 plant and animal species that are listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act, more than any other estuary in North America.[1] .

Habitat

Because the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary is located in an area where tropical and temperate climates meet, it's over 4,000 plant and animal species include native subtropical and tropical residents, plus many migratory winter visitors. The estuary's diverse habitats, including freshwater tributaries, spoil islands, salt marshes, seagrass flats, oyster bars, mangroves, shorelines, and sandy pine forests provide homes for both aquatic and terrestrial plants and animals.

Flora

Mangrove forests provide shoreline protection, water purification, and nurseries for small fish, shrimp and crab. Seagrass is a keystone indicator species for the overall health of the lagoon.

Fauna

The estuary serves as a spawning and nursery ground for many different species of salt and brackish water fish and shellfish. Aquatic animals such as alligator, sea turtle, dolphin, Florida manatee and saltwater fish forage in the seagrass flats. Black drum, Red drum, Spotted seatrout, Common snook, and Atlantic tarpon are the main gamefish found in the estuary's lagoons.

Nearly 1/3 of the nation's manatee population lives in the estuary or migrates through the area seasonally. Between 200 and 800 Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) live year-round in the Mosquito, Banana River and Indian River lagoons.[3] At night the lagoons are lit up with bioluminescent dinoflagellates in the summer and ctenophore in the winter.

In the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, a world-class birding destination, many types of shorebirds, waterfowl and wading birds, like the Roseate spoonbill, Snowy egret, and Brown pelican, can be seen feeding on shrimp, crustaceans and mollusks near the shorelines and mangrove covered spoil islands. Birds of prey including kites, hawks, osprey, owls, and eagles feed on reptiles, rodents and fish.

Higher up, in the sandy palmetto and pine uplands, the terrestrial animals might include boar, bobcat, deer, raccoon, opossum, armadillo, Gopher tortoise and Florida scrub jay.

Economy

A healthy estuary is a vital economic factor in Florida's East Coast communities.

Direct Income

The Indian River Lagoon provides direct income for those working both on, and off the water.

- Commercial fishing

- Ecotourism Industry: Fishing, Hunting and Tour Guides

- Watercraft/Auto sales, rentals, service and fuel

- Fish Camps, Marinas and Ports

- Outdoor Equipment, Bait and Tackle vendors

- Fishing and Hunting License sales fund Florida's wildlife conservation projects.

Indirect Income

The economic success of direct income industries also indirectly increases income for:

- Tourist Destinations

- Visitor Transportation: Airport, Rental Car, Limo, Shuttle, Uber, Fuel and Service

- Hospitality: Hotel, Restaurant, Gift & Souvenir Shops, Convenience Stores

- Vacation rentals and Real Estate sales

A 2016 IRL Economic Valuation Study, conducted by Hazen and Sawyer water consultants for the St. John Water Management District (SJWMD), estimated the Indian River Lagoon Estuary's economic value at $7,640,311,564 per year.[4]

History

During glacial periods, the ocean receded. The area that is now the lagoon was grassland, 30 miles from the beach. When the glacier melted, the sea rose. The lagoon remained as captured water.

The indigenous people who lived along the lagoon thrived on its fish and shellfish. This was determined by analyzing the middens they left behind, piled with refuse from clams, oysters, and mussels.

The Indian River Lagoon was originally known on early Spanish maps as the Rio de Ais, after the Ais Indian tribe, who lived along the east coast of Florida. An expedition in 1605 by Alvero Mexia resulted in the mapping of most of the lagoon. Original place names on the map included Los Mosquitos (the Mosquito Lagoon and the Halifax River), Haulover (current Haulover Canal area), Ulumay Lagoon (Banana River) Rio d' Ais (North Indian River), and Pentoya Lagoon (Indian River Melbourne to Ft. Pierce)

Early European settlers drained the swamps to raise pineapples and citrus. They dug canals discharging freshwater into the lagoon at five times the historical volume.

Prior to the arrival of the railroad, the river was an essential transportation link.

In 1896 and 1902, there were fish kills in the lagoon from gas from the muck below.

The advent of the automobile, starting in the 1930s, resulted in causeways which diverted the sluggish flow of the waterway. Huge population influx resulted in sewage, and stormwater runoff from roadways, polluting the lagoon.

From 1989 to 2013, the population along the lagoon increased by 50% to 1.6 million people.

Timeline

In 1916, the St. Lucie Canal (C-44) diverts excess nutrient-rich water from Lake Okeechobee into the South Indian River Lagoon. While this helps prevent life-threatening flooding in the Okeechobee area, it creates toxic blooms after entering the Lagoon, a threat to flora, fauna, and humans. This situation is proving difficult to address in the 21st century.

From 1913 to 2013, activity by humans has increased the watershed for the lagoon from 572,000 to 1,400,000 acres increasing runoff of freshwater and nutrients from farms. Both have been detrimental to lagoon health. The wetlands are needed to cleanse the lagoon. About 40000 acres of land were lost to mosquito control and have been restored, but by 2013, recovery was incomplete.

Mangroves are a keystone species that help prevent shoreline erosion and provide critical habitat for marine life. Between the 1940s and 2013, 85% of them had been removed for housing development.

In 1986, there were 46 sewer plants along the 156 mile lagoon. They discharged about 55,000,000 gallons daily into the estuary.

In 1990, the Florida Legislature passed the Indian River Lagoon Act, requiring most sewer plants to stop discharging into the lagoon by 1996.

Some sports fish rebounded in population in the 1990s when gill nets were banned and pollution in the lagoon was reduced. In 1995 the seagrass covered over 100,000 acres.[5]

In 2007, concerns were raised about the future of the lagoon system, especially in the southern half where frequent freshwater discharges seriously threatened water quality, decreasing the salinity needed by many fish species, and have contributed to large algae blooms promoted by water saturated with plant fertilizers. In the mid 1990s, the lagoon has been the subject of research on light penetration for photosynthesis in submerged aquatic vegetation.[6]

In 2010, 3,300,000 lbs of nitrogen and 475,000 lbs of phosphorus entered the lagoon.

In 2011, a superbloom of phytoplankton resulted in the loss of 32,000 acres of lagoon seagrass. In 2012, a brown tide bloom fouled the northern lagoon.

Catches of blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) dropped unevenly from 4265063 lb in 1987 to 389,795 lb in 2012, but with high catches in 1998, 1991, alternating with low catch years. These crabs require 2% salt content in the water to survive. Drought increases the salt content and heavy rainfall decreases it. Both of these conditions have recurred over the past decades and are believed to have had an adverse effect on the crab population.[7]

In 2013, algae blooms and loss of sea grass destroyed all gains.

In 2013, four major problems with lagoon water quality were identified.

- Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from runoff from the application of fertilizer;

- an estimated 8 to 11% septic tank failures of tens of thousands of septic tanks in the county.

- Muck from construction, farming, erosion, and dead plants find their way to the bottom of the lagoon, preventing growth and consuming vital oxygen essential to marine flora and fauna;

- Invasive species, including the Asian green mussel, South American charru mussel, and the Australian spotted jellyfish (Phyllorhiza punctata), eat clams and fish larvae.

In 2016, there were an estimated 300,000 septic tanks in the five-county area bordering the Lagoon.

In 2018, lagoon health is better near ocean inlets. Pollution is worse in areas with no inlets, such as the Mosquito Lagoon, North IRL, and the Banana River.

Human Impact

The Indian River Lagoon National Estuary spreads across Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach counties with a rapidly growing population of 1.5 million residents. Waterfront residents enjoy a panoramic view, a parade of watercraft, wildlife encounters, and backyard boat docks with instant water access. Condominium dwellers enjoy well-manicured landscaping, large paved parking lots, and a convenient shopping plaza nearby.

Over twenty causeways and bridges have been built across the estuary to accommodate an ever increasing barrier island population. The estuary's water is primarily moved by wind, and every causeway impedes nature's ability to refresh the lagoon's stagnant water. Detritus piles up at the causeway corners, rots in the summer heat, and makes the Indian River smell like rotten eggs.

Human impact from excessive development, inadequate sewer utilities, seeping septic systems, stormwater run-off laden with lawn fertilizer, and the destruction of wetlands for development has drastically affected the estuary's health.

The result of this adverse human impact could be seen in a 2016 green algae outbreak. Fueled by nutrient pollution, the blooming algae growth created a lack of oxygen (eutrophication) in the water that caused widespread fish kills across Florida's East Coast. The resulting harmful algae bloom (HAB) rendered parts of the estuary unusable; turned lush waterfront real estate into least desirable neighborhoods; created respiratory health problems for residents; killed many aquatic plants and animals; and totally devastated the local ecotourism industry; all known effects of excessive nutrient pollution.

Restoration and Preservation

Hazen and Sawyer's Economic Valuation Study also reported that for every $1 spent restoring the Indian River lagoon, $33 would be returned to the local economy.[4]

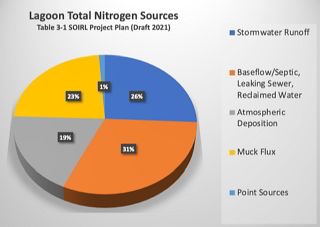

In 2016, the citizens of Brevard County voted in a .5% sales tax increase to fund a program to restore and preserve the Indian River Lagoon. Brevard's Save Our Indian River Lagoon (SOIRL) trust has received over $114 million in sales tax revenue to date (2019). Directed by the Brevard County Natural Resources Department, overseen by the Citizen Oversight Committee (COC), counseled by the NEP's IRL Council[8], and guided by scientists from the Indian River Lagoon Research Institute (IRLRI) at Florida Institute of Technology (FIT), the SOIRL currently has several restoration projects underway.[9]

The 2019 SOIRL Project Plan[10] includes:

- Research and Monitoring by IRLRI and SJRWMD

- Muck dredging

- Septic tank to sewer system conversion

- Barrier island sewer utility overhaul

- Living Shoreline and oyster bar restoration

- Public information campaigns on fertilizer and stormwater impact

Web Links

- Florida Today: From the Water - Healing our Lagoon

- EPA - National Estuary Program

- NEP - Indian River Lagoon Council

- SJRWMD - Indian River Lagoon

- Brevard County - Save Our Indian River Lagoon

- Brevard Zoo - Restore Our Shores

- Indian River Lagoon Species Inventory

- NOAA Estuary Education Kit

- EPA - Watershed Academy

Documents

- Indian River Lagoon - An Introduction to a National Treasure (PDF 40pp 4.09MB)

- Keri Smith - An Overview of the Indian River Lagoon (PDF 22pp 930KB)

- 2016 IRL Economic Valuation Report (PDF 69pp 3MB)

- 2016 IRL Economic Valuation Brochure (PDF 2pp 3MB)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 An Introduction to a Natural Treasure

- ↑ IRLNEP_Final-Draft-CCMP-REVISION_2018-12-07 (PDF 196pp 20MB), "2016 EXPANSION OF THE IRLNEP PLANNING BOUNDARY", page 14, retrieved 2021-04-14.

- ↑ Indian River Lagoon Estuarine System Stock - Bottlenose Dolphin

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 2016 IRL Economic Impact Report

- ↑ Seagrass biodiversity in the Indian River Lagoon

- ↑ Hanisak, M. Dennis (1997). "Continuous Monitoring of Underwater Light in Indian River Lagoon: Comparison of Cosine and Spherical Sensors". In: EJ Maney, Jr and CH Ellis, Jr (Eds.) the Diving for Science…1997, Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences, Seventeenth Annual Scientific Diving Symposium. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- ↑ Waymer, Jim (September 8, 2013). "Lagoon crab catches dwindle". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 1A, 3A. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Website of the IRL Council". onelagoon.org. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ↑ Save Our Indian River Lagoon

- ↑ SOIRL Project Plan 2019