Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[Category:National Wildlife Refuge]] | [[Category:National Wildlife Refuge]] | ||

[[Category:Brevard County | [[Category:Brevard County]] | ||

[[Category:Volusia County | [[Category:Volusia County]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:28, December 26, 2021

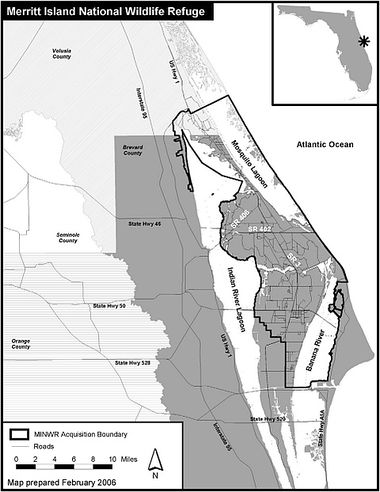

The Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge traces its beginnings to the development of the nation’s Space Program. In 1962, NASA acquired 140,000 acres of land, water, and marshes adjacent to Cape Canaveral to establish the John F. Kennedy Space Center. NASA built a launch complex and other space-related facilities, but development of most of the area was not necessary. In 1963 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) signed an agreement to establish the refuge and in 1975 a second agreement established Canaveral National Seashore. Today, the Department of Interior manages most of the unused portions of the Kennedy Space Center as a National Wildlife Refuge and National Seashore.[1]

Location

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge is due east of Titusville, Florida on SR406.

Coordinates: (28 38' 29.28" N, 80 44' 9.03" W) GPS: (28.641467, -80.735842)

History

About 7,000 years ago, the last glaciers retreated, sea level increased, and the barrier island and lagoons that now form Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge were created. Just inland from the barrier island, these Paleo-Indians were the earliest inhabitants of the Indian River Lagoon region. The descendents of these peoples settled in the area and made their living off the vast resources of the Indian River Lagoon, the St. Johns River, and the surrounding uplands. By 2000 BC, the earliest Americans were making pottery and weapons of stone, shell, and animal teeth and still survived as hunter/gatherers, although rising sea levels had reduced the size of the peninsula to roughly its current size. Eventually, distinct tribes known today as Ais and Timucuans formed and lived along the shores of the Indian River, leaving behind evidence including huge mounds of discarded shellfish, animal bones, and fractured pottery. From these mounds, much has been learned about these peoples and their way of life.

The first contacts between North American Indians and European explorers likely occurred in 1513 when Juan Ponce de Leon encountered Ais Indians in a village near Cape Canaveral. During this era, Spanish explorers were frequently shipwrecked along the Florida coast. These contacts brought great changes to the Ais culture and by the time a permanent Spanish settlement occurred in St. Augustine in Florida in 1565, the Ais were viewed as fierce warriors. Eventually, disease, warfare, and malnutrition led to the demise of these early cultures.

For the next 200 years, the population of Florida grew slowly and ethnicity of the inhabitants became more diverse. What is known today as Brevard County was a part of Mosquito County until Florida officially became a state in 1845. The county was first named St. Lucie and spread southward to Dade County. Several other boundary changes occurred until 1959 when Brevard attained the present-day boundaries.

One of the few settlers of the Titusville area prior to the Civil War was Douglas Dummitt who moved to the area from Tomoka where he was the postmaster and a sugarcane farmer in the 1820’s and 1830’s. Douglas was also one of the few planters to cultivate oranges and sold his first orange crop in 1828. While still living in Tomoka, he began experimenting with various techniques of citrus cultivation by planting wild sour-orange trees that had likely originated with the Spanish and acclimated to the Florida soil and climate. He grafted cuttings from sweet orange trees – purportedly from groves planted by the Turnbull colonists at New Smyrna – to sour-orange root stock. These experimental trees survived the famous 1835 freeze and were transplanted to the Dummitt Grove (now a part of Merritt Island NWR) following the Second Seminole War. Dummitt increased the size of his grove over the years and by 1859 was producing an estimated 60,000 oranges a year. He contributed to the development of the Indian River citrus region by selling budwood to other growers to start new groves in the region. Dummitt died at his orange grove in 1873, after having made many significant contributions to the political and economic development of the Indian River region.

The year 1854 brought a significant event to the area: the spit of land between the Indian River and Mosquito Lagoon that had been used as a “haul over” for centuries was officially improved and opened. This was one of the first major man-made improvements to the inland waterway system that had served Florida travelers since pre-historic times. At that time, the haul over measured approximately one-third of a mile long, 10-12 feet wide, 3 feet deep, and was primarily used by shallow draft vessels. Further improvements to the canal began in 1885 and the work was completed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930’s. Today, Haulover Canal is a part of the Intercoastal Waterway and is used by thousands of vessels annually to travel between the Mosquito Lagoon and Indian River on their trek up and down the east coast. Fishermen and paddlers also use the Canal in large numbers.

Overall, little significant development occurred in the region from the late 1920’s until after World War II. Shortly after the war began, a period of rapid growth stimulated in part by the development of the United States space industry complex at Cape Canaveral, occurred. The quest for space use and exploration began in 1950 with the establishment of a missile testing range at Cape Canaveral. At that time, the United States federal government already owned the land surrounding the Cape Canaveral lighthouse. The government acquired the remaining acreage necessary for the facility from private land owners. In 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration began operations at the cape. NASA’s primary function was to launch communication, meteorological, and scientific satellites. NASA vaulted to the forefront nationally in 1961 when President John F. Kennedy announced plans to place a man on the moon before the end of the decade.

In 1963, the federal government acquired 140,000+ acres north and west of the Cape on Merritt Island where a major support facility for the launch complex – the John F. Kennedy Space Center – would be developed. Kennedy was right – on July 20, 1969, man stepped on the face of the moon. The first Space Shuttle mission, STS-1 (Space Transportation System) was launched April 12, 1981. The Columbia orbited the Earth 36 times in the 54.5 hour mission. This was the first U.S. manned space flight since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975.

When NASA purchased the land that is now the refuge, several families lived here and farmed the lands. Remnants of old foundations and canals are visible at various locations, especially near Haulover Canal.

On August 28, 1963, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service entered into an Interagency Agreement with NASA to manage all lands within the Kennedy Space Center that are not currently being used for NASA KSC operations. These lands, known today as the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, provide habitat for more than 1,500 species of plants and wildlife. With an excellent long-term working relationship among NASA, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service, this unique area is a shining example of how nature and technology can peacefully co-exist.[2]

Purpose

According to it's 2008 Comprehensive Conservation Plan, the FWS opts to take a landscape view of the refuge and its resources, focusing refuge management on wildlife and habitat diversity.[3]

- The refuge would support 500–650 Florida scrub-jay family groups with 350–500 territories in optimal condition across 15,000–16,000 acres.

- With active management, the refuge would support

- 11–15 nesting pairs of bald eagles;

- maintain 6.3 miles of sea turtle nesting beaches;

- and maintain 100 acres of habitat for the southeastern beach mouse.

- Manatee-focused management would be reestablished on the refuge.

- Several impoundments would be managed for wood storks.

- The refuge would manage 15,000–16,000 acres of impounded wetlands for waterfowl.

- More than 2,500 acres of wetlands would be managed for shorebirds and another 1,500 acres would focus on wading birds.

- An increased effort to control exotic plants and animals would be made.

- Coastal islands would be restored. Environmental education would be increased, with greater emphasis on diversity of habitats and global warming.

- Coordination and partnerships would be enhanced.

The wildlife and habitat vision for National Wildlife Refuges stresses that wildlife come first; that ecosystems, biodiversity, and wilderness are vital concepts in refuge management.

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge's primary goals are:

- To provide habitat for migratory birds.

- To provide habitat and protection for endangered and threatened species.

- To provide habitat for natural wildlife diversity.

- To provide opportunities for wildlife-dependent recreation including hunting, fishing, wildlife observation and photography, environmental education, and interpretation.

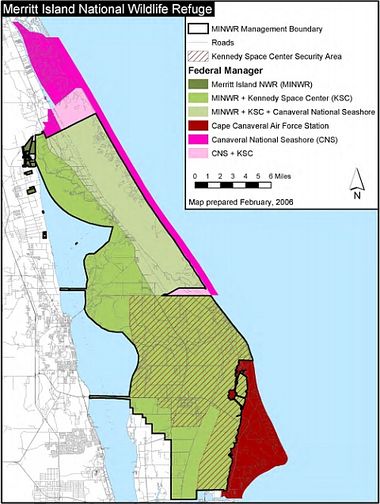

Government

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge is administered under a unique arrangement between the FWS, NPS, Space Force and NASA. As a member of the National Wildlife Refuge System, part of the refuge is governed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, under the U.S. Department of Interior. The eastern boundary of the refuge is the National Park Service's Canaveral National Seashore. The MI NWR is bounded on the south by the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Large portions of both wildlife sanctuaries lie on Kennedy Space Center property, and fall under NASA's jurisdiction. All four Federal government organizations work together to manage the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge.