Pelican Island Prologue: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

by William Reffalt, FWS Volunteer, February 2003 | by William Reffalt, FWS Volunteer, February 2003 | ||

[https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/Region_4/NWRS/Zone_2/Everglades_Headwaters_Complex/Pelican_Island/Images/History/XX%20The%20First%20Refuge%20is%20born.pdf Pelican Island Prologue - FWS (PDF 13pp 779KB)] | Source: [https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/Region_4/NWRS/Zone_2/Everglades_Headwaters_Complex/Pelican_Island/Images/History/XX%20The%20First%20Refuge%20is%20born.pdf Pelican Island Prologue - FWS (PDF 13pp 779KB)] | ||

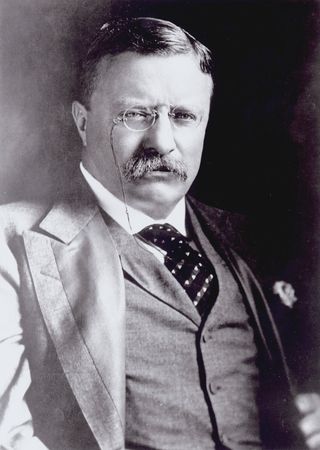

From a historical perspective, it is important to note that reserving Pelican Island, creating the first unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System, was not an instantaneous brainstorm of President Theodore Roosevelt, as astute as he was. Actions by persons to protect birds over a century ago ultimately contributed to T.R.’s bold commitment to an American wildlife and habitat conservation system. | From a historical perspective, it is important to note that reserving Pelican Island, creating the first unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System, was not an instantaneous brainstorm of President Theodore Roosevelt, as astute as he was. Actions by persons to protect birds over a century ago ultimately contributed to T.R.’s bold commitment to an American wildlife and habitat conservation system. | ||

Revision as of 09:16, November 9, 2020

Prologue to Pelican Island

by William Reffalt, FWS Volunteer, February 2003

Source: Pelican Island Prologue - FWS (PDF 13pp 779KB)

From a historical perspective, it is important to note that reserving Pelican Island, creating the first unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System, was not an instantaneous brainstorm of President Theodore Roosevelt, as astute as he was. Actions by persons to protect birds over a century ago ultimately contributed to T.R.’s bold commitment to an American wildlife and habitat conservation system.

Frank Chapman Proposes to Buy Pelican Island and Protect Its Pelicans

Pelican Island is located in Florida’s Indian River about 45 miles south of Cape Canaveral, lying close inside the barrier island protecting the coastline in this area. Dr. Henry Bryant of Boston, an especially active ornithologist of the period, discovered its ornithological merits during several visits to Florida in 1854-1858. His description is informative, “I found (brown pelicans) breeding in larger and larger numbers as I went north (from Key West), until I arrived at Indian River, where I found the most extensive breeding-place that I visited; this was a small island, called Pelican Island, about 20 miles north of Fort Capron. The nests here were placed in the tops of mangrove trees, which were about the size and shape of large apple-trees. Breeding in company with the Pelican were thousands of Herons, Peale’s Egret, the Rufous Egret and Little White Egret…and Roseate Spoonbills; and immense numbers of Man-of-War Birds and White Ibises were congregated upon the island, and probably bred there at a later period than my visit.”

Other 19th Century visitors, escaping rigorous northern winters, described the island as, “draped in white, its trees seemingly covered with snow….” (Owing to the downy young pelicans and other white birds perched atop the whitewashed nests and mangroves.

In late 1900, Frank Chapman talked to William Dutcher and Theodore Palmer about buying Pelican Island, thereby enabling protection for the island’s wildlife. Chapman, a bird curator at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, author of many bird books, and founder of Bird-Lore (the Audubon Societies’ magazine), was an active member of the American Ornithologist’s Union (AOU). He had visited Pelican Island during nesting seasons in 1898 and 1900 (the 1898 visit coincided with his honeymoon; his bride was enlisted to skin and prepare a pelican series) to photograph the brown pelicans and study nesting attributes and colony success. Palmer was an Assistant Chief in the Division of Biological Survey, U.S. Department of Agriculture (DOA), charged with implementing the Lacey Act of 1900 to protect birds. Palmer, a key member of the AOU Committee on the Protection of North American Birds also became involved in the resurgent Audubon Societies, a movement committed to halting the wanton slaughter of innocent bird life for thriving markets. Chapman wanted Palmer to research the steps for purchasing the island from the State of Florida (however, his assumption about state ownership was wrong; it was soon determined that the island was federal public land).

In April 1901, Palmer was asked to go to Tallahassee by Dutcher, Chairman of the AOU Bird Protection Committee, to meet with the Legislature and seek passage of the “AOU model law” to protect non-game birds. Before 1901 only five States had effective laws for non-game birds. During 1901, the Committee (primarily Dutcher and Palmer) obtained passage of adequate laws in eleven States, including Florida. Palmer, an expert in wildlife legislation, often had to make adjustments in the model law to accommodate individual states’ needs. Florida’s new law was enacted June 4, 1901, and its passage enabled the AOU Committee to hire wardens with money from the “Thayer Fund” to protect important Florida bird colonies. Those “nurseries” were being systematically devastated by gunners paid by middle-men merchants making a living selling feathers, birds, and parts, mostly to New York markets.

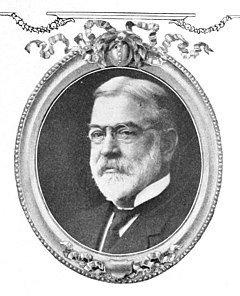

Profile of William Dutcher, a Key Figure in the Pelican Island Reservation

William Dutcher (1846-1920), an insurance agent in New York City, and Theodore Palmer each performed tasks vital to obtaining the Executive Order setting aside Pelican Island, America’s first National Wildlife Refuge. Their efforts deserve our recognition and appreciation.

William Dutcher’s energetic leadership in revitalizing the flagging Audubon Societies movement at the beginning of the 20th Century epitomizes volunteerism. Dutcher had a passion, fostered by self-education and his friends, for natural history—especially life histories and protection of birds. He held charter membership on the AOU Bird Protection Committee, and served as Chairman in 1896-97 and from 1899-1905. He participated in the first Audubon movement begun in 1886 by Forest and Stream Editor George Bird Grinnell. In 1902 Dutcher led in the establishment, and became Chair of the Audubon Societies’ National Committee.

In spite of considerable strain on his business, Dutcher fostered the bird protection cause on many fronts—legislative, administrative, law enforcement, and by dissemination of popular and scientific information. With Palmer, he initiated, lobbied for, and gained passage of laws protecting non-game birds in more than 40 States. Dutcher received no remuneration for his work on behalf of birds.

Women’s fashions of the time generated huge demands for birds and their parts and caused particular destruction to those nesting in colonies. That, and making fans, ink quills, decorative mats, wall hangings, and footwear of the bird parts, had created markets in New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, London and Paris by the 1850s. Quantitative records, spotty and often not comparable, record several hundred thousand birds sold at weekly auctions. Feathers and parts from peacocks, rheas, ostriches, pheasants and birds of paradise came from sources in Africa, Asia, Indonesia and Europe. Parts from herons, kingfishers, jays, magpies, and others were supplied from South and Central America, and Florida. Gulls, terns and many shorebird species were obtained from northeastern Atlantic island colonies extending from Virginia to Labrador. Many highly sought species, such as sea swallows (terns) were locally extirpated rapidly. Leading ornithologists feared a new series of extinctions loomed on the horizon.

The situation, as the AOU Bird Protection Committee began its work in 1884, looked as unstoppable as the precipitant demises of the “endlessly abundant” Carolina parquets, passenger pigeons, and great auks, or the American bison. Although states had developed increasingly complex game laws and in some instances had hired wardens to enforce those laws, those advocating protection for the over 80 percent of North America’s bird species unprotected by game laws faced an enormous, daunting task.

By 1886, that Committee developed a “Model Law” based on defining game birds, and then protecting all other taxonomic Orders and some Families. The approach eliminated confusion, resistance from sporting interests and state game commissions, and greatly improved chances of passage by state legislatures. It also could accommodate differing state-by-state opinions about several species. Thus, mourning doves, blackbirds, raptors and a handful of other species were left unprotected in some states while protected in most.

The Committee issued special bulletins, made lanternslide presentations, gave newspaper interviews, and developed special museum exhibits describing the destruction of bird rookeries, thus pioneering techniques to gain public support to stop the slaughter. During the first half of the 1890s however, Committee actions slowed, its members were discouraged and weary. In November 1895, William Dutcher first assumed the reins of leadership, and infused the other members with new enthusiasm and commitment.

Florida’s Pelican Island, during most of that time, remained beyond the Committee’s horizon. In those early days the concept of protection and the procedures for implementing it were not yet in focus. It remained for the AOU Committee, especially Dutcher and Palmer, to pioneer such elements and to convince people of the need to apply them.

Pelican Island: A Vital and Threatened Nesting Ground

Pelican Island lies 45 miles south of Cape Canaveral in the south flowing lagoon called Rio d’Ais by the Spanish, but renamed Indian River by the English in the 1760s. The island’s northern reach rests a bit south of the navigation channel as it flows into “the narrows,” a well known stretch of this popular waterway along the inside shore of South Florida’s barrier islands.

Pelican Island had a distinctly triangular shape according to J.O. Fries’ July 1902 cadastral survey for the AOU Committee, with each side measuring roughly 700 feet. A General Land Office survey in 1903 calculated its area at 5.5 acres.

Given the numbers of birds and the array of species found on the island by Dr. Henry Bryant, it is apparent that this was an ancient nursery for birds, occupied for centuries if not millennia. Given the growing bird markets to the north, and the universal feeling that all of America’s natural resources were first for food and then any other use that benefited man, the island’s avian inhabitants were already feeling gunning pressure when Bryant visited in the 1850s. Bryant noted that roseate spoonbills were in such numbers at Pelican Island that one person killed 60 in a day. These were likely sold for making decorative fans in St. Augustine.

Following Bryant’s 1859 report, others appeared in the major periodicals of the day. In 1871, Mr. S. C. Clarke reported in American Naturalist, “A party of hunters visited (Pelican Island) this year in March, and found it covered with eggs and young birds, which were being fed by the old ones with fish. Some of these were shot, and most of the others driven away, when suddenly the island was invaded by multitudes of the Fish Crow…which began to devour both the eggs and the callow young…. The hunters then turned their guns upon the crows and slaughtered them in heaps, before they would abandon their prey.”

Dr. James Henshall, a physician who took patients to Florida for its climate and the recuperative powers of outdoor recreation, published Camping and Cruising in Florida in 1884. Under Pelican Island -- Slaughter of the Innocents he wrote, “As we passed we saw a party of northern tourists at the island, shooting down the harmless birds by the scores through mere wantonness. As volley after volley came booming over the water, we felt quite disgusted at the useless slaughter, and bore away as soon as possible and entered the narrows.”

Scientists and naturalists regularly visited the island for specimens, usually attempting to take a “series” of plumages (meaning 18 or more pelicans for each collector), and “sets” of eggs. One oologist (bird-egg specialist) admitted taking 125 sets after halting, and discarding, his guide’s collection made by filling pails indiscriminately with eggs, without reference to sets.

More published reports exist, while the unrecorded attrition caused by passengers and crews of the regular steamboats obviously diminished the birds even more. Whistles were often blown as the steamboats entered or exited the narrows and the alarmed birds immediately took to the air, circling outward from the island. That placed them within gun range, when tourists and crew blasted away merely for the “fun of killing.”

Mrs. F.E.B. Latham and Frank Chapman, Both Helped Save Pelican Island

History is often a story of people. Pelican Island’s protection came from people with far thinking recognition of this special place and its important wildlife values, and their bold commitment to conserving those values in perpetuity. When Frank Chapman visited Pelican Island in 1898 the thousands of herons, egrets, roseate spoonbills, man-o-war birds, and white ibises were gone, and the pelicans severely reduced. Chapman’s studies and keen interest in the island and the pelicans prevented their extirpation on that tiny, but obviously significant, native bird habitat.

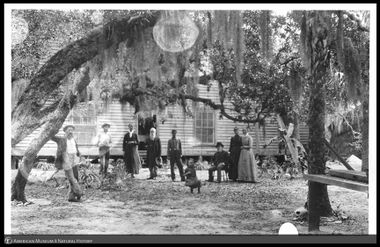

Mrs. F.E.B. “Ma” Latham, who with her husband Charles ran Oak Lodge, a boarding house about nine miles up the Indian River from Pelican Island, helped influence events contributing to its reservation and later incidents. Oak Lodge was first built about 1881 and rapidly became a magnet for scientists, naturalists, museum curators and artists wanting to observe and document the natural history conditions in Florida before dramatic changes occurred. Notable guests included William Beebe, William Hornaday, Louis Aggasiz Fuertes, Frank Chapman, Outram Bangs, Herbert Job, Arthur Bent, and George Shiras III, among others.

Using Oak Lodge as their base, they sallied forth making observations, securing collections and obtaining data for subsequent journal articles, museum exhibits, collections, and personal presentations. While together at the lodge they enjoyed a collegial intellectual stimulation, thereby enhancing the value to the institutions supporting winter stays of up to several months. Florida was a cornucopia of wildlife species and frontier-like conditions that they believed would soon degrade, hence the urgent drive to inventory and document its animal and plant life.

Chapman described Ma Latham as a “born naturalist” having “great enthusiasm and energy” for the work of collecting and processing specimens. She favored these men and their specialized work, wanting to make her lodge a resort for scientific people. Her most notable feat was the collection of several sets of loggerhead turtle eggs, and embryos, each day after their laying to the end of incubation, sixty days later. This required daily trips to the beach, ¾ mile away, plus searching for, digging up, preserving, documenting and tagging each specimen. The turtle egg laying season also attracted numerous black bears on and near the beach, making the trips more than mere strolls. She ultimately sold the sets for $25 each, clearly a bargain considering the time and effort involved. Mrs. Latham made particularly favorable and lasting impressions on Frank Chapman and William Hornaday, Director of the New York Zoological Park, a very influential person in wildlife conservation during 1875-1935.

Frank Chapman began a career as a banker, but didn’t find the personal and intellectual rewards he sought from a life’s endeavors. In March 1888, he accepted the museum job under Dr. Joseph A. Allen, after volunteering for several months helping to sort collections, and, thereafter, he never looked back. Chapman quickly became a leader in the bird conservation movement, an important author and editor, and an innovator in interpreting nature within a museum context. He pioneered the use of photographic equipment to document natural history objects and their context for several phases of museum work.

Chapman first visited Pelican Island in 1898 upon the recommendation of Mrs. Latham, while on his honeymoon. He initiated a detailed study of the nests, eggs and other features of this single remaining brown pelican colony on the Atlantic coast. He returned in 1900 with improved photographic equipment and a commitment to replicate his earlier study. The results indicated a 14% decline in the pelican population.

In 1894, when he chaired the AOU Bird Protection Committee, Chapman had learned about some individuals in Massachusetts and New York having committed to patrol important gull and tern nesting colonies after obtaining protective laws, and thereby rebuilding depleted colonies. He reported that success to the AOU in 1895, and William Dutcher took the lesson to heart.

Early in 1900, bird dealers’ demands for gull and tern skins, feathers, and parts far exceeded the supply, and that encouraged new assaults on rookeries. Abbott Thayer, an artist and avid bird protectionist, appealed to the public and his friends for donations to employ guards for protecting bird colonies during the breeding season. His efforts were successful and, by previous agreement, AOU committee chair Dutcher used the money to hire wardens. The “Thayer Fund,” as it became known, helped the bird protection cause enter a new, more aggressive phase.

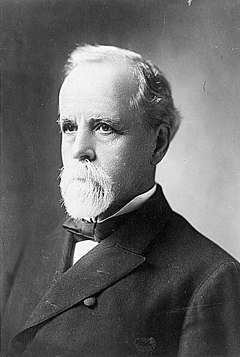

Theodore Palmer, a Key Player in Creating Our First Refuge.

William Dutcher often told others, “I do nothing without first consulting Palmer.” Theodore Sherman Palmer was, by 1900, a recognized expert in wildlife legislation. Whenever Dutcher went to lobby a state for passage of the AOU model law, he wanted Palmer to be there. If it became necessary to accommodate a state’s parochial view of species such as mourning doves, flickers, or bobolinks, Palmer fashioned language satisfying that need while retaining the basic thrust for protection. Dutcher and Palmer, sometimes with help from other Committee members, gained passage of the AOU model law, or close variant, in 23 states between 1901-04.

Palmer was 21 years old in 1889 when he arrived in Washington to be an assistant to Dr. C. Hart Merriam, Chief of the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy (later the Biological Survey) in the Department of Agriculture. Palmer had graduated from the University of California the previous year, but agreed to interrupt graduate studies after he met and was offered a position in the expanding Division by Merriam. Like other Merriam assistants, Palmer demonstrated an interest in ornithology (he was admitted to the AOU in 1888), regional biological surveys, and Merriam’s life-zone theories. Soon after reporting for work he became involved in the biological survey of Death Valley and adjacent areas, and was placed in charge of that expedition when Merriam was sent to the Pribilof Islands in Alaska for urgent analysis.

Palmer earned a Medical Degree in 1895 from Georgetown University, emulating Merriam and co-worker A.K. Fisher. Palmer was designated Assistant Chief in 1896 (the year it was renamed Division of Biological Survey), a role that lasted until 1902 when Merriam hired long time friend Henry Henshaw as his primary Assistant. Merriam (and other assistants) habitually took to the field each spring and summer, devoting as much time as possible to field studies away from Washington. Designated as Acting Chief during those extended periods, Palmer became thoroughly involved in the Division’s work, including the intricacies of legislative affairs. His willingness to brave the muggy DC summers, along with enviable work habits and diligent adherence to Merriam’s guidance made him the repeated choice for Acting Chief. Palmer’s published works of the period show increasing involvement in non-game bird protection work, and state and federal wildlife legislation.

According to William Hornaday, a Dean of the conservation movement, “Dr. Palmer is a man of incalculable value to the cause of protection. No call for advice is too small to receive his immediate attention, no fight is too hot and no danger-point too remote to keep him from the fray. Wherever the Army of Destruction is making a particularly dangerous fight to repeal good laws and turn back the wheels of progress, there will he be found.”

In 1896 the Supreme Court issued its Geer v. CT decision. Although it recognized possible constitutionally based and superior federal authority in wildlife matters, that opinion was used to form a state ownership doctrine, giving impetus for state legislation and claims of primacy in fish and game matters. Throughout the following half century, Geer would be whittled away, and finally vacated altogether by the Supreme Court. Given its perceived leaning toward the states, it is noteworthy that only a few months after Geer v CT was issued, federal legislation affecting wildlife was initiated. First came the “Lacey Bill” on July 1, 1897, followed a day later by the “Teller Bill,” and, in 1898, the “Hoar Bill.” Each invoked the Commerce Clause to provide federal authority over wildlife, and all failed to pass over several sessions of Congress.

The Lacey Act became law on May 25, 1900, modified substantially from its original version and ultimately containing elements from the Hoar and Teller bills. It specifically enlarged the Agriculture Department’s powers, “…to include the preservation, distribution, introduction, and restoration of game birds and other wild birds. The Secretary of Agriculture is hereby authorized to adopt such measures as may be necessary to carry out the provisions of this act….”

Paul Kroegel, the First Warden in Charge of Pelican Island.

William Dutcher’s 1902 report to the AOU explained actions taken in Florida following passage of the 1901 non-game bird protection law. His AOU Committee had engaged four wardens in 1902, using money from the Thayer Fund. In March, Dutcher had written Mrs. Latham, at Chapman’s suggestion, to find a reliable man in Sebastian, FL to guard Pelican Island’s birds. Latham engaged Paul Kroegel in April; he was paid $50 by the Committee to protect the birds during the nesting season. Mrs. Latham was also engaged by Dutcher in an oversight capacity to go to Pelican Island several times during 1902.

Paul Kroegel (1864-1948) was born in Chemnitz, Germany and came to America at the age of 6 with his father and brother. After 10 years in the Chicago area, where Paul apprenticed in carpentry, the Kroegels moved to Florida, finally reaching New’s Haven (later renamed Sebastian) in 1881. Kroegel family history explains that the homestead was selected by Paul’s father because of a large (1000 ft. long by 400 ft. wide by 70 ft. high) Indian shell mound that reminded him of hills near Chemnitz. The family’s first shelter was located on the mound and, soon thereafter, their first home. History has it that “Barker’s Bluff,” as the mound was called, was named for an early trader killed by Indians dissatisfied with his overly watered whiskey.

Paul Kroegel soon turned to boat building, constructing a shop and dock on the homestead, and he also earned a Master’s License to operate a cargo hauler and trading vessel between Titusville and Key West. “Captain Paul” was welcomed for his lively accordion and the prospects of an impromptu dance the night of his arrival, as well as for the goods he brought to many small, isolated communities. According to family tradition, Paul spent many hours each week studying the graceful pelicans flying above the triangular island 1.5 miles across the lagoon from Barker’s Bluff because they reminded him of the storks near Chemnitz.

Paul was noted for industriousness, perseverance, and innovation. He was civic-minded and a solid family man. He was unusually resourceful and able to grasp both mechanical and academic subjects quickly and successfully. Ma Latham could hardly have found a better person to take on the demanding and potentially dangerous task of guarding the pelican colony and vital nesting habitat. As Paul knew, and Dutcher would soon learn, the unusually extended breeding season at Pelican Island required his devoted attention for six months of the year, or more.

It also became discouragingly obvious to these committed men that the island’s land status created a very difficult enforcement situation. At that time Florida appointed county wardens, usually selected more for their political connections than for devotion to the law. The authority granted by the AOU Committee worked well under private ownership. It insured trespass control and enhanced a court’s sense of justice in convicting those also violating state law by killing innocent, often beneficial, birds found on private property. With Pelican Island’s ownership in question, however, trespass was a moot issue in the courts, and the bird protection law had no provision against mere harassment.

Dutcher’s January 1903 report declared, “As it is important that this colony should always be protected, it has been deemed advisable to get legal possession of it, and to that end your Committee has had it surveyed and has taken all the necessary steps to purchase the island…. It is hoped that before the next breeding season is reached the A.O.U. will have absolute control of the island as owner in fee simple.” Indeed, Dutcher’s legal representative, Robert Williams, Jr., had applied to Florida’s Surveyor General. Neither of them imagined the red tape, informational demands, or uncertainty they would face, owing to the laws for transferring federal public lands to private ownership. As he delivered his report, Dutcher was likely buoyed by thoughts of having completed work on numerous requests for information and by a sense of certainty that final action could not be far away. Such thoughts would soon be dissipated by reality.

The Reservation Alternative to Purchase Suddenly Arises.

In 1890, Interior Secretary John Noble asked the Attorney General under what statute the President might reserve public lands. Assistant Attorney General Shields responded with a thorough review of Supreme Court opinions and numerous precedents of the executive making reservations in the public interest. He concluded, “There is no specific statutory authority empowering the President to reserve public lands; but the right of the executive to place such lands in reservation, as the exigencies of the public service may require…is recognized and maintained in the courts. The reservation of public lands from disposition may be effected either by proclamation or executive order.” Noble adopted that opinion and it became policy for the General Land Office (GLO), although little known beyond that agency.

About 12 ½ years later, in February 1903, AOU Committee Chair William Dutcher pressed his friend and colleague Theodore Palmer in Washington, DC about efforts to purchase Pelican Island and protect its bird colony, “Will it not be possible for you…to go to…Interior, in order to hurry up the Pelican Island matter?” Six days later Dutcher wrote again from his New York City office mentioning the red tape being encountered and the considerable amount of information, affidavits, and the cadastral survey he and Robert Williams had already supplied to the GLO. He concluded, “So far as I know, I have complied with the requirements…and am now waiting, and hoping….” He urged Palmer to expedite matters.

Palmer responded on Feb. 21, 1903 with details of the meeting, “Mr. Bond and I called on the Commissioner…and went over the whole question. [He] promised…to facilitate the survey of the island…[and] this will be the crucial point in the whole transaction.” Palmer described the many twists, turns, and uncertainties in the process to achieve fee ownership. It was not a satisfying picture. Dutcher must have felt deep frustration. Palmer’s last paragraph, however, suddenly opened a new possibility, “Still another solution of the question is to have the island set apart as a government reserve. I find that we can have this done by executive order at short notice, and if the request is made before any claims are filed it will effectually shut out all comers.” Palmer suggested that, if Dutcher agreed, he should address a letter to the Secretary of Agriculture requesting that Pelican Island be made a government reservation.

Dutcher’s draft letter reached Palmer on Tuesday February 24th, pointing out that the AOU Committee would “gladly continue to employ a paid warden.” He requested the reservation include “three small islands…in Indian River, Florida.” Palmer responded immediately that the research to verify federal ownership did not apply to the other islands; the request had to be confined to Pelican Island, and needed to be in Palmer’s hands by Thursday evening. Dutcher’s letter, dated Feb. 26 was on AOU Committee letterhead, and contained the changes.

Palmer wrote Dutcher the next day saying the letter had reached him “at 9:10 and at 10:30 the Department’s letter on the same subject was mailed to the Department of the Interior.” Secretary Wilson’s letter (written by Palmer) to DOI Secretary Hitchcock referenced the authority vested in the Department of Agriculture by Section 1 of the Lacey Act, “[To] adopt such measures as may be necessary for the preservation of game and other wild birds.” Wilson’s letter located the island, declared it to be of no agricultural value but of substantial importance, for many years, to brown pelicans and other water birds and presently the only remaining pelican breeding grounds along the entire east coast of Florida. He observed, “the colony affords opportunities for the study of bird life under exceptionally favorable circumstances….” Warning of dangers to the birds, he summarized Chapman’s data from 1898 and 1900 showing a 14% population decline to 2,364 birds. Wilson concluded, “I urgently recommend that this matter receive prompt attention…and this Department be enabled to accord the birds protection during the present spring. Dutcher’s letter was enclosed.

Final Events Leading to Pelican Island National Bird Reservation.

President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Executive Order on Saturday, March 14, 1903 withdrawing Pelican Island as America’s first National Bird Reservation. Notable in his action was the absence of a specific statute authorizing him to create such a reservation for birds. Roosevelt used “implied Presidential powers” recognized by the courts, but of uncertain merit in the Congress.

In his 1913 autobiography, written soon enough after his departure from office to provide important perspectives on events still vivid in his memory, TR explained his action. “Even more important [than actions he had taken under several statutes] was the taking of steps to preserve from destruction beautiful and wonderful wild creatures whose existence was threatened by greed and wantonness…. The creation of [51 bird reservations] at once placed the United States in the front rank in the world work in bird protection…. I acted on the theory that the President could at any time in his discretion withdraw from entry any of the public lands of the United States and reserve the same for…public purposes.” Roosevelt well knew of his initial signature’s significance, and the importance of his many subsequent orders enlarging the new series of reservations to preserve wild birds and other animals in the public interest. Unquestionably, Theodore Roosevelt earned and deserves recognition as the “Father of America’s National Wildlife Refuge System.”

Another notable feature in the events leading to TR’s action March 14, 1903 was the sudden, almost belated, manner in which the reservation idea came to Palmer and Dutcher’s attention, and its rapid utilization to accomplish their goal. The Bird Protection Committee had been pursuing the island’s protection for nearly three years but, until the weekend of February 21, 1903, their intent was to purchase it. On the day before, Theodore Palmer and Frank Bond, representing the Committee, met with DOI’s new GLO Commissioner, William Richards, accompanied by Public Surveys Division Chief Charles DuBois. Most of the meeting was used to discuss the Committee’s long efforts to acquire the island, additional information needs, and the likely ensuing events once an official survey was filed. Richards, past Governor of Wyoming, had taken the oath of office barely a month before the meeting, but he knew Frank Bond well, and therefore promised to facilitate matters. Still, the outlook was not good; existing law favored homestead entries over other applicants. A homestead filing at any time would defeat the AOU Committee’s application; the island and its pelicans could quickly be lost.

As the meeting ended, DuBois revealed the alternative of using Presidential authority to withdraw the island as a bird reservation. DuBois was familiar with the Attorney General’s opinion, adopted by DOI in 1890, supporting that power with precedents and Supreme Court decisions. As an entirely new idea to the AOU members, it required that they seek a decision from Chairman Dutcher. Appraised of the new alternative, Dutcher worked over the weekend drafting a request to the Secretary of Agriculture. His request, received in DC on February 27th, was forwarded the same day to the Interior Department. The Executive Order was signed two weeks later. In that brief interval the Secretary of Agriculture had to approve and sign the request, the Secretary of the Interior had to be briefed and approve the decision, and, following development of documents for the White House, the President had to be briefed and decide favorably. Given today’s norm for handling public requests, those two weeks constitute an unbeatable speed record.

Roosevelt’s autobiography offers further insight on his decisions, “The course I followed, of regarding the Executive as subject only to the people, and, under the Constitution, bound to serve the people affirmatively in cases where the Constitution does not explicitly forbid him to render the service, was substantially the course followed by both Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln.” As our Nation prepares to celebrate the Centenary of his Pelican Island action next year, we can be especially thankful that “Teddy” took that course.

Today, America’s National Wildlife Refuge System is unsurpassed in size and scope anywhere in the world, and Pelican Island continues to be the preferred nesting grounds for hundreds of pelicans and hundreds more birds of other species—a notable conservation area ready to begin another 100 years of service to wildlife and the public.

Epilogue: More Roosevelt Reservations, Foundations For a System.

The alternative of using implied Presidential powers to reserve Pelican Island, rather than pursue its purchase, was revealed to its proponents only two weeks before it was used to create Pelican Island National Bird Reservation, the first unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The future possibilities flowing from the revelation, and the groundwork that it required, took a little more time to mature. The second National Bird Reservation, Louisiana’s Breton Island, was established in November 1904, a year and a half after Pelican Island. Stump Lake Bird Reservation in North Dakota followed in March 1905, and before the end of that year three more Executive Orders were signed (Huron Islands and Siskiwit in Michigan, and Passage Key in Florida). By then, William Dutcher, still Chair of the AOU Committee and the person who had asked for the Pelican Island order, published his first report as the first President of the newly incorporated National Association of Audubon Societies (NAAS). He declared, “If the National Association did no other work than to secure Bird Reservations and to guard them during the breeding season, its existence would be fully warranted…. One of our wardens reports that it is a wonderful sight to see the thousands of Ducks and Geese that gather on the islands and the reservation waters in his charge. ” (Report from Breton Island’s warden, William Sprinkle) Migratory ducks and geese thus became recognized as prominent and proper denizens of the government bird reservation, even though the focus of the AOU Committee, and NAAS after 1905, remained non-game bird protection until the 1913 Migratory Bird Act.

In 1906, John Lacey, Chairman of the House Public Lands Committee, achieved passage of a law “To protect birds and their eggs in the game and bird preserves” bestowing protection, needed management authority, and Congressional recognition on the Bird and Mammal Reservations. The Act facilitated more reservations, and his Committee’s Report, No. 1469, also explicitly recognized the substantial values of the reservations to ducks and geese.

By 1907, NAAS field agents were investigating, documenting and proposing qualified areas to Dutcher and to Frank Bond, who had become Chief Clerk in the GLO. Seven reserves were established that year, but the deluge came in the fiscal year that President Roosevelt would leave office (7/1/08-6/30/09); thirty-six refuges were created that year, bringing his total to 51 bird and 2 mammal reservations administered by Agriculture’s Bureau of Biological Survey.

Roosevelt’s establishment of the congressionally authorized (35 Stat.267) National Bison Range in Montana was noteworthy. That refuge marks the first U.S. conservation unit entirely purchased by the federal government. The Biological Survey selected the area from three sites evaluated by noted University of Montana zoologist, Morton Elrod, as potential bison reserves. The National Bison Range, with essentially unchanged boundaries, has achieved its purposes admirably and continues as a monument to foresight, planning and careful management.

Close review of Roosevelt’s reservations demonstrates the focus on non-game bird protection, but also traces concept expansion to include game birds. The enlarged concept led, in 1909, to reserving areas surrounding reservoirs to protect expected concentrations of ducks and geese, as well as other water-fowl (Originally “water-fowl” encompassed all species associated with water, including terns, grebes, herons, ibises, pelicans, etc.; today “waterfowl” means ducks, geese, and swans). The reservoir refuge idea belongs to Frank Bond, an AOU/NAAS member who worked for the Reclamation Service in DC prior to his General Land Office tenure. In the GLO, Bond positioned himself, first as Chief of the Drafting Division and then as Chief Clerk, to receive, gain approval for, and write the Executive Orders for the Bird Reservations.

Fire Island Moose Reservation was Roosevelt’s only mammal reservation using implied Presidential authority, although it was after the 1906 Statute. The island, in Cook Inlet offshore from Anchorage, was an important moose wintering area. It later became a military reservation and eventually was permanently removed from the refuge system.

The Yukon Delta Bird Reservation in Alaska also deserves special recognition. Even authors associated with Refuges and the Fish and Wildlife Service have overlooked its establishment in 1909. Yet, the reserve’s hugely important nesting grounds encompassed more than 8 million acres. Neither its acreage nor its long list of species and gigantic numbers of birds produced annually are recorded in reports about the early reserves. Revoked in 1922 for political reasons, small portions of the area were reestablished in 1960-61. In 1980, Congress created an even larger Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge (over 19.3 million acres) atop and surrounding Roosevelt’s Reservation, validating the merits of his original decision.

A Note from the Author on Sources of Information for the Prologue to Pelican Island

Below is a general description of sources of information used for this essay.

Records for Dutcher, Palmer, Chapman, and other involved associates came from the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress and the Audubon Society Archives, NY City Library in the form of correspondence, articles, reports, and manuscripts by and between the principals in the series. The AOU Bird Protection Committee’s annual reports, published in Auk, 1896-1904, and related reports, editorials and articles in Bird-Lore, 1899-1910, report and describe the actions, events and intentions of the involved parties. Information on the plumage trade in NY, Chapman’s visits to Pelican Island, and information on the AOU Committee and the Audubon movement, also came from Bird-Lore, and from the autobiographies of Chapman (1933), T.G. Pearson (1937). Reports of the Chief of the Biological Survey (and its predecessors), the USDI and GLO provided official information on several elements of the Prologue series.

Chapman’s Bird Study With a Camera (1900, 1914), and Camps and Cruises of an Ornithologist (1908) document his Pelican Island studies, and details about the island and its birds. The 1859 report by Henry Bryant describes the birds of Pelican Island. Altogether, the Prologue series author compiled a bibliographic list of over 200 titles on Pelican Island, and a large proportion of them are in his files. The libraries at Sebastian and Vero Beach, FL, provided Kroegel family records and histories written by them as well as other detailed history information regarding Pelican Island. Previous FWS news articles and the historical records of that agency and its processors were extensively consulted. The legislative histories of the Lacey Act (1900) and “An Act to protect birds and their eggs in the game and bird preserves” (1906) describe those laws and their purposes. Numerous other bills, amendments, hearings and reports related to wildlife protection, and the designation of areas for their protection were consulted at the DOI and DOA Libraries in DC, while some related materials were obtained at the Library of Congress. Roosevelt’s observations and explanations came from his autobiography (1913), and published articles related to his involvement in bird and mammal protection.

A complete bibliographic list would include scores of books, monographs, journal and magazine articles, government and organizational reports, manuscripts, and personal letters covering the time period 1842-1929. In addition, the Spanish, French and English histories of the general area of Pelican Island were researched as far back as any records exist (ca 1659) at the Library ofCongress, plus the archeological and paleontological records in the vicinity of the island.