Southeastern Beach Mouse: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references> | |||

<ref name="FNAI_2001">[https://www.fnai.org/FieldGuide/pdf/Peromyscus_polionotus_niveiventris.pdf Peromyscus polionotus niveiventris FNAI 2001 (PDF 2pp 55KB)]. Retrieved 2022-01-29.</ref> | <ref name="FNAI_2001">[https://www.fnai.org/FieldGuide/pdf/Peromyscus_polionotus_niveiventris.pdf Peromyscus polionotus niveiventris FNAI 2001 (PDF 2pp 55KB)]. Retrieved 2022-01-29.</ref> | ||

| Line 193: | Line 194: | ||

<ref name="CDC_1996">Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 1996. Hantavirus in the United States: a brief review. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Document #0994929. 15 November 1996.</ref> | <ref name="CDC_1996">Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 1996. Hantavirus in the United States: a brief review. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Document #0994929. 15 November 1996.</ref> | ||

</references> | |||

<references | |||

{{IRL footer estuary|cat=Biota}} | {{IRL footer estuary|cat=Biota}} | ||

Revision as of 08:24, January 30, 2022

The Southeastern beach mouse (Peromyscus_polionotus_niveiventris) is an oldfield mouse subspecies that is only found on Florida's Atlantic coast barrier island between Volusia and Martin counties.

Description

The Southeastern beach mouse has a light brown and grayish back side, light brown forehead, and white belly. Tails are white on top and gray on the bottom. Adult males average a length of 5.3 inches while females have an average length of 5.5 inches. Females have a 2.2 inch tail while males have a two inch tail.[1]

Taxonomy

Peromyscus polionotus is a member of the order Rodentia and family Cricetidae. The southeastern beach mouse is one of 16 recognized subspecies of oldfield mice P. polionotis [2]; it is one of the seven of those subspecies that are called beach mice. The southeastern beach mouse was first described by Chapman[3] as Hesperomys niveiventris. Bangs[4] subsequently placed it in the genus Peromyscus, and Osgood[5] assigned it the subspecific name P. polionotus niveiventris.

Distribution

The oldfield mouse (P. polionotus) is distributed throughout dry, sandy habitats on inland sites in northeastern Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Seven subspecies of the oldfield mouse occur on beaches and dunes of the Atlantic coast of Florida and the Gulf coast of Alabama and Florida, and are collectively known as “beach mice”.

Five subspecies of beach mice occur on the Gulf coast from Mobile Bay, Alabama to Cape San Blas, Florida: the Alabama beach mouse (Peromyscus polionotus ammobates), the Perdido Key beach mouse (P. p. trissyllepsis), the Choctawhatchee beach mouse (P. p. allophrys), the Santa Rosa beach mouse (P. p. leucocephalus) and the St. Andrews beach mouse (P. p. peninsularis); the latter four occur on the Gulf coast of Florida. The Anastasia Island beach mouse (P. p. phasma) and the southeastern beach mouse occur on the Atlantic coast of Florida, but their ranges do not overlap.

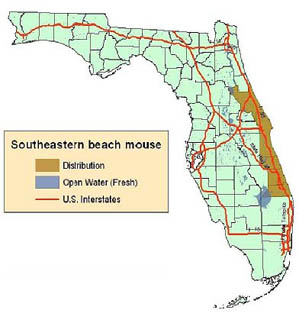

Historically, the southeastern beach mouse occurred along about 280 km of Florida's southeast coast, from Ponce Inlet, Volusia County, southward to Hollywood, Broward County, and possibly as far south as Miami Beach in Miami-Dade County, Florida[6]. The type locality for the southeastern beach mouse is East Peninsula, Oak Lodge, opposite Micco, Brevard County, Florida[5]. Based on the most recent published literature, this subspecies is currently restricted to about 80 km of beach, occurring in Volusia County, Brevard County, and scattered locations in Indian River and St. Lucie counties (Figure 1). The southeastern beach mouse is geographically isolated from all other subspecies of P. polionotus.

Habitat

Essential habitat of the southeastern beach mouse is the sea oats (Uniola paniculata) zone of primary coastal dunes.[7][8][6] This subspecies has also been reported from sandy areas of adjoining coastal strand vegetation[9][10][11], which refers to a transition zone between the foredune and the inland plant community.[12] Although individuals can occur and reproduce in the ecotone between the former sea oats zone and the shrub zone, they will not survive as a population there.[13] Beach mouse habitat is heterogeneous, and distributed in patches that occur both parallel and perpendicular to the shoreline.[10] Because this habitat occurs in a narrow band along Florida's coast, structure and composition of the vegetative communities that form the habitat can change dramatically over distances of only a few meters.

Primary dune vegetation described from southeastern beach mouse habitat includes sea oats, dune panic grass (Panicum amarum), railroad vine (Ipomaea pes-caprae), beach morning glory (Ipomaea stolonifera), salt meadow cordgrass (Spartina patens), lamb's quarters (Chenopodium album), saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), and camphor weed (Heterotheca subaxillaris).[9][14] Coastal strand and inland vegetation is more diverse, and can include beach tea (Croton punctatus), prickly pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa), saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera), rosemary (Ceratiola ericoides), sea grape (Coccoloba uvifera), oaks (Quercus sp.) and sand pine (Pinus clausa).[10]

Although Extine[9] observed this subspecies as far as 1 km inland on Merritt Island, he concluded that the dune scrub communities he found them in represent only marginal habitat for the southeastern beach mouse; highest densities and greater survival of mice were observed in beach habitat. In the same study site, Extine[9] and Extine and Stout[10] reported that the southeastern beach mouse showed a preference for areas with clumps of palmetto, sea grape, and expanses of open sand. In Indian River County, southeastern beach mice inhabit dunes that are only 1 to 3 m wide and dominated by sea oats and dune panic grass.[15] According to Stout[6], southeastern beach mice do not occur in areas where woody vegetation is greater than 2 m in height.

Within their dune habitat, beach mice construct burrows to use as refuges, nesting sites, and food storage areas. Burrows of P. polionotus, in general, consist of an entrance tunnel, nest chamber, and escape tunnel. Burrow entrances are usually placed on the sloping side of a dune at the base of a shrub or clump of grass. The nest chamber is formed at the end of the level portion of the entrance tunnel at a depth of 0.6 to 0.9 m, and the escape tunnel rises from the nest chamber to within 2.5 cm of the surface.[16] A beach mouse may have as many as 20 burrows within its home range. They are also known to use old burrows constructed by ghost crabs (Ocypode quadrata).

Foraging

Beach mice typically feed on seeds of sea oats and dune panic grass.[16] The southeastern beach mouse probably also eats the seeds of other dune grasses, railroad vine, and prickly pear cactus. Although beach mice prefer the seeds of sea oats, these seeds are only available as food after they have been dispersed by the wind. Beach mice also eat small invertebrates, especially during late spring and early summer when seeds are scarce.[17] Beach mice will store food in their burrows.

Behavior

Not much is known about the life history and ecology of the southeastern beach mouse. Therefore, this section makes inferences about their biology using data from studies of other beach mice.

P. polionotus is the only member of the genus that digs an extensive burrow for refuge, nesting, and food storage.[17] To dig the burrow, the mouse assumes a straddling position and throws sand back between the hind legs with the forefeet. The hind feet are then used to kick sand back while the mouse backs slowly up and out of the burrow.[17] Burrows usually contain multiple entrances, some of which are used as escape tunnels. When mice are disturbed in their burrows, they open escape tunnels and quickly flee to another burrow or to other cover.[17]

Beach mice, in general, are nocturnal. They are more active under stormy conditions or moonless nights and less active on moonlit nights. Movements are primarily for foraging, breeding, and burrow maintenance. Extine and Stout[10] reported movements of the southeastern beach mouse between primary dune and interior scrub on Merritt Island, and concluded that their home ranges overlap and can reach high densities in their preferred habitats.

Reproduction and Demography

Studies on Peromyscus species in peninsular Florida suggest that these species may achieve greater densities and undergo more significant population fluctuations than their temperate relatives, partially because of their extended reproductive season.[18] Subtropical beach mice can reproduce throughout the year; however their peak reproductive activity is generally during late summer, fall, and early winter. Extine[9] reported peak reproductive activity for P. p. niveiventris on Merritt Island during August and September, based on external characteristics of the adults. This peak in the timing and intensity of reproductive activity was also correlated to the subsequent peak in the proportion of juveniles in the population in early winter.[9] This pattern is typical of other beach mice as well.[19]

Sex ratios in beach mouse populations are generally 1:1.[9][19] Blair[16] indicated that beach mice are monogamous; once a pair is mated they tend to remain together until death. He also found, however, that some adult mice of each sex show no desire to pair.

Nests of beach mice are constructed in the nest chamber of their burrows a spherical cavity about 4 to 6 cm in diameter. The nest comprises about one fourth of the size of the cavity and is composed of sea oat roots, stems, leaves and the chaffy parts of the panicles.[20]

The reproductive potential of beach mice is generally high.[17] In captivity, beach mice are capable of producing 80 or more young in their lifetime, and producing litters regularly at 26-day intervals.[21] Litter size of beach mice, in general, ranges from two to seven, with an average of four. Beach mice reach reproductive maturity as early as 6 weeks of age.[17]

Dispersal of young mice and the disappearance of adults may be the primary reasons for population fluctuations in certain area.[16] Young beach mice move an average of 432 m before establishing residence in a new area. Although reproductive potential is high, mortality of adult beach mice is also quite high. Only 19.5 percent of the beach mice present in Blair's study in January survived to May of that same year.

Relationship to Other Species

Southeastern beach mice co-occur with cotton mice (P. gossypinus) and cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus), although local distributions and population variations may not be related.[9] It is unknown whether these species compete for food resources. Recent trap efforts south of Sebastian Inlet in Indian River County indicate that cotton mice are more prevalent in the coastal strand habitat, rather than the dune habitat preferred by the beach mouse. Ivey[20] also states that cotton mice occur in a variety of vegetative communities, but prefer wooded and more mesic habitats. Cotton rats, however, are prevalent in both dune and coastal strand habitat.

Southeastern beach mice probably interact with house mice (Mus musculus), particularly in disturbed habitats where house cats are present. Humphrey and Barbour (1981) speculated that competitive exclusion by house mice was a factor in the extinction of the pallid beach mouse. Frank and Humphrey[7] discuss the potential threat of house mice to the Anastasia Island Beach mouse, and Briese and Smith[22] found that house mice competed with P. polionotus in Georgia for available habitat when the Peromyscus population became reduced because of disturbance or predation.

As stated previously, beach mice dig burrows in the dune; however, they are also known to occasionally use old burrows constructed by ghost crabs. In South Florida, the coastal habitat is also used by four species of endangered or threatened sea turtles; where the southeastern beach mouse occurs these are predominantly the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) and the green turtle (Chelonia mydas). From an ecosystem perspective, conservation efforts should be implemented to benefit all of these species simultaneously, and management activities should avoid any potential conflict between these species.

Predation is the primary cause of mortality of adult beach mice.[16] Known and probable predators of the southeastern beach mouse include snakes, bobcats (Lynx rufus), gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), raccoons (Procyon lotor), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius), armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), owls, hawks, great blue herons (Ardea herodias), red-imported fire ants, and domestic cats and dogs.

Status and Trends

The distribution of the beach mouse is extremely limited due to modification and destruction of its coastal habitats. Along Florida's Gulf coast, the Alabama beach mouse, the Perdido Key beach mouse, and the Choctawhatchee beach mouse were federally listed as endangered in 1985. The St. Andrews beach mouse was federally listed as endangered in 1998. On the Atlantic coast of Florida, the Anastasia Island Beach mouse (P. p. phasma) and the southeastern beach mouse were federally listed as endangered and threatened, respectively, in 1989 (54 FR 20602). One additional subspecies, the pallid beach mouse (P. p. decoloratus), was formerly reported from two sites on the Atlantic coast, but extensive surveys conducted since 1959 provide substantial evidence that this subspecies is extinct.[23]

The distribution of the southeastern beach mouse has declined significantly, particularly in the southern part of its range. Historically, it was reported to occur from Ponce (Mosquito) Inlet, Volusia County, to Hollywood Beach, Broward County.[2] Bangs[4] reported it as extremely abundant on all the beaches of the east peninsula from Palm Beach at least to Mosquito (Ponce) Inlet. More recently, the southeastern beach mouse has been reported only from Volusia County (Canaveral National Seashore to about 11 km north of the Volusia-Brevard County line), Federal lands in Brevard County (Canaveral National Seashore, Merritt Island NWR, and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station), a few localities in Indian River County (Sebastian Inlet SRA, Treasure Shores Park, and several private properties), and St. Lucie County (Pepper Beach County Park and Fort Pierce Inlet SRA).[8][24][25][15].

Large, healthy populations of the southeastern beach mouse are still found on the beaches of Canaveral National Seashore, Merritt Island NWR, and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Brevard County-all federally protected lands.[26][27] The distribution of this subspecies in the South Florida Ecosystem, however, is severely limited and fragmented. There are not enough data available in South Florida to determine population trends for the southeastern beach mouse; however, recent surveys reveal that it occurs in very small numbers where it is found.

In Indian River County, the Treasure Shores Park population has experienced a significant decline over the past few years, and it is uncertain whether populations still exist at Turtle Trail or adjacent to the various private properties.[28] Trapping efforts during the past 6 years in this area have documented a decline from an estimated 300 individuals down to numbers in the single digits.[13] The status of the species south of Indian River County is currently unknown. No beach mice were found during recent surveys in St. Lucie County; it is possible that this species is extirpated there. The southeastern beach mouse no longer occurs at Jupiter Island, Palm Beach, Lake Worth, Hillsboro Inlet or Hollywood Beach. Given these data and trends, it is likely that without management intervention the entire South Florida population of southeastern beach mice will be lost in the near future.

The primary threat to the survival and recovery of the southeastern beach mouse is the continued loss and alteration of coastal dunes. Large-scale commercial and residential development on the Atlantic coast has eliminated beach mouse habitat in Palm Beach and Broward counties. This increased urbanization has also increased the recreational use of dunes, and harmed the vegetation essential for dune maintenance. Loss of dune vegetation results in widespread wind and water erosion and reduces the effectiveness of the dune to protect other beach mouse habitat.

In addition to increased urbanization, coastal erosion is responsible for the loss of the dune environment along the Atlantic coast, particularly during tropical storms and hurricanes. The construction of inlets has exacerbated coastal erosion problems along the Atlantic coast. There are six man-made inlets on the Atlantic coast from Brevard County to Broward County that disrupt longshore sediment transport; because of this disruption beach habitat is gained on the north side of an inlet and becomes severely eroded immediately to the south. In Indian River County, for example, erosion has been nearly 2 m per year at Sebastian Inlet SRA (just south of Sebastian inlet); this is six times the average erosion rate for the county.[29] Erosion of the dune habitat adjacent to the Treasure Shores Park has accelerated by nearly 0.3 m per year over the past 10 years.[30]

The encroachment of residential housing onto the Atlantic coast increases the likelihood of predation by domestic cats and dogs. A healthy population of southeastern beach mice on the north side of Sebastian Inlet SRA in Brevard County was completely extirpated by 1972, presumably by feral cats.[31] Urbanization of coastal habitat could also lead to potential competition of beach mice with house mice and introduced rats.

Management

Southeastern beach mice live in a dynamic, harsh environment that is exposed to recurring tropical storms. Historically, beach mice populations fluctuated in response to changes in the environment. In the past, local populations probably became extinct when storms destroyed their habitat; these areas were then recolonized by adjacent populations that survived the storms. Today, however, increased urbanization along the Atlantic coast has eliminated much of the coastal dune and created isolated patches of habitat available to the beach mouse.

Ongoing management practices within the range of the southeastern beach mice restrict beach access to designated crossovers (boardwalks) to minimize the human trampling of the dune systems. Since public beaches on Florida's east coast receive heavy public use, continuing to enforce these restrictions on dune access will be essential to the recovery of the southeastern beach mouse.

Beach nourishment projects are conducted periodically by the COE to maintain the beach in areas of greatest erosion. Southeastern beach mice could be adversely affected if dredged sand is placed on or near their habitat. It is critical that effects to beach mice also be evaluated for any land-modification projects in coastal habitat, and that any dredged material be compatible with existing beach sand.

Although there are a number of State and county regulations pertaining to residential, commercial and recreational development in coastal areas, none specifically address protection of beach mouse habitat. The regulations dictate requirements for siting and construction of buildings, utilities, and access corridors.

The Coastal Barriers Resources Act of 1982, as amended (16 U.S.C. 3501 et seq.) prohibits the expenditure of Federal funds that encourage development within the undeveloped, unprotected 186 units of the Coastal Barriers Resources System (CBRS); however, construction in these units is still proceeding, even with no Federal involvement. Examination of aerial photographs for 157 CBRS units revealed a 40.7 percent increase in the number of structures between 1982 and 1986/1988. Over half of this construction occurred in the State of Florida.[32]

Habitat fragmentation has created disjunct, isolated populations of southeastern beach mice in South Florida. Although the populations of P. p. niveiventris in Brevard County are large and healthy because they are protected on public lands, they are geographically, and thus genetically, isolated from populations in Indian River County because of Sebastian Inlet. No natural dispersal can occur from Brevard County populations to enhance the populations to the south. The five inlets between Indian River and Broward counties also create unnatural barriers to dispersal along this length of coast. As a result of this isolation, southeastern beach mouse populations are probably now ephemeral and have a high risk of extinction.

The long-term persistence of a given population may depend on the ability of mice from adjacent parts of the range to recolonize beaches. To avoid excessive risks of extinction from demographic, catastrophic, or genetic events, an attempt should be made to establish viable populations of southeastern beach mice in remaining areas of suitable habitat throughout their historic range. Although population viability analyses (a technique to estimate the probability of survival, for various time periods, of animal populations of differing effective breeding size) have not been done for beach mice, relocation experiments with other subspecies of beach mice have been successful. However, due to the limited amount of habitat available along the Atlantic coast, it may be difficult to establish new populations of P. p. niveiventris with good prospects for long-term survival. Three sites in South Florida that warrant evaluation as potential recipient sites are Fort Pierce Inlet SRA, Avalon SRA, and Pepper Beach County Park in St. Lucie County.

If translocation projects are attempted, proven reintroduction protocols should be followed. Holler et al.[33] successfully re-established the Perdido Key beach mouse by translocating 15 pairs from Gulf State Park at Florida Point in Alabama to an unoccupied site at Gulf Islands National Seashore. Frank[34] successfully translocated 55 Anastasia Island beach mice (27 females and 28 males) from two locations on Anastasia Island to a site at Guana River SP where the subspecies had been extirpated. In general, it is recommended that the source population of mice for a translocation come from a large, healthy population, and that the release site be an area that is protected and unoccupied. It is also recommended to move mice during the fall season when more food is available. Monitoring of the introduced population will determine whether additional augmentation is needed. In addition, once the translocated population is stable, mice should be exchanged with the donor population.[35]

The State of Florida administers land acquisition programs that can be used to secure coastal dune habitat for the southeastern beach mouse and other endemic species. Reintroduction of this species into these protected areas, and managing the areas to avoid invasion by exotic vegetation and depredation of mice by domestic animals, may help to ensure the survival and recovery of the beach mouse over the long term. Likewise, the Archie Carr NWR was established in 1989 to protect beach habitat along a 20-mile section of coast in Brevard and Indian River counties. An ecosystem approach to coastal resource protection is being employed to link the beach and dune habitats, maritime forests, wetlands, and estuarine systems. As proposed, the refuge would protect four segments of Atlantic beach and dunes totaling 14.9 km.

Surveys to determine the status of the southeastern beach mouse in the South Florida Ecosystem in areas of suitable habitat are imperative. Monitoring protocols exist that suggest trapping should be conducted twice per year, early to mid-fall and late winter. A trapping protocol to determine presence/absence of beach mice has been standardized, and is included with each collecting permit issued by the GFC and FWS. This protocol describes how sampling should be done, and the appropriate number of traps to use. It also requires that material (such as cotton batting) be placed in traps when nighttime temperatures are forecast to be < 18.5 degrees C, and that traps be checked beginning at 11:00 p.m. when nighttime temperatures are forecast to be < 10 degrees C.

It is important to note that hantavirus is now a concern when trapping rodents. In Florida, the cotton rat has been identified as a carrier for the virus causing hantavirus pulmonary syndrome.[36] There have been no documented cases of hantavirus associated with beach mice work; however, because cotton rats may be present when trapping for beach mice, precautions should be taken to minimize the likelihood of exposure.