Johnson's Seagrass

Johnson's seagrass was the first, and only, marine plant species to be listed under the Endangered Species Act.

About Johnson's Seagrass

Johnson's seagrass (Halophila johnsonii) plays a major role in the health of "benthic" (anything associated with or occurring on the bottom of a body of water) resources as a shelter and nursery habitat. Johnson's seagrass is the first—and only—marine plant species to be listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).[1]

Johnson’s seagrass is rare and exhibits one of the most limited geographic distributions of any seagrass. Within its limited range (lagoons on the east coast of Florida from Sebastian Inlet to central Biscayne Bay), it is one of the least abundant species. Because of its limited reproductive capacity (apparently only asexual) and limited energy storage capacity (small root-rhizome structure and high biomass turnover), it is less likely to be able to repopulate an area when lost due to anthropogenic or natural disturbances.[2]

Habitat

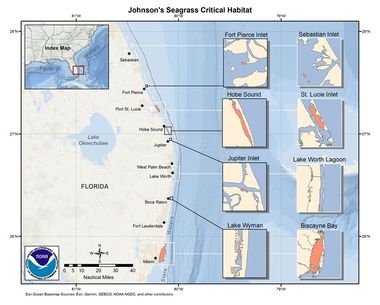

According to the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the distribution of Johnson's seagrass is limited to the east coast of Florida from central Biscayne Bay (25°45′ N. lat.) to Sebastian Inlet (27°51′ N. lat.). There have been no reports of healthy populations of this species outside this range.

Within this range, 10 areas are designated as critical habitat: a portion of the Indian River Lagoon, north of the Sebastian Inlet Channel; a portion of the Indian River Lagoon, south of the Sebastian Inlet Channel; a portion of the Indian River Lagoon near the Fort Pierce Inlet; a portion of the Indian River Lagoon, north of the St. Lucie Inlet; a portion of Hobe Sound; a site on the south side of Jupiter Inlet; a site in central Lake Worth Lagoon; a site in Lake Worth Lagoon, Boynton Beach; a site in Lake Wyman, Boca Raton; and a portion of Biscayne Bay.[3]

NMFS has determined that the essential areas and features described here are at risk and may require special management consideration or protection. Special management may be required because of the following activities:

(1) Vessel traffic and the resulting propeller dredging and anchor mooring; (2) dredging; (3) dock, marina, and bridge construction and shading from these structures; (4) water pollution; (5) land use practices including shoreline development, agriculture, and aquaculture.

Activities associated with recreational boat traffic account for the majority of human use associated with the critical habitat areas. The destruction of the benthic community due to boating activities, propeller dredging, anchor mooring, and dock and marina construction was observed at all sites during a study by NMFS from 1990 to 1992. These activities severely disrupt the benthic habitat, breaching root systems, severing rhizomes, and significantly reducing the viability of the seagrass community. Propeller dredging and anchor mooring in shallow areas are a major disturbance to even the most robust seagrasses. This destruction is expected to worsen with the predicted increase in boating activity. Trampling of seagrass beds, a secondary effect of recreational boating, also disturbs seagrass habitat. Populations of Johnson's seagrass inhabiting shallow water and water close to inlets, where vessel traffic is concentrated, will be most affected.

The constant sedimentation patterns in and around inlets require frequent maintenance dredging, which could either directly remove essential seagrass habitat or indirectly affect it by redistributing sediments, burying plants and destabilizing the bottom structure. Altering benthic topography or burying the plants may remove them from the photic zone.

Permitted dredging of channels, basins, and other in-and on-water construction projects cause loss of Johnson's seagrass and its habitat through direct removal of the plant, fragmentation of habitat, and shading. Docking facilities that, upon meeting certain provisions, are exempt from state permitting also contribute to loss of Johnson's seagrass through construction impacts and shading. Fixed add-ons to exempt docks (such as finger piers, floating docks, or boat lifts) have recently been documented as an additional source of seagrass loss due to shading (Smith and Mezich, 1999).

Decreased water transparency caused by suspended sediments, water color, and chlorophylls could have significant detrimental effects on the distribution and abundance of the deeper water populations of Johnson's seagrass. A distribution survey in Hobe and Jupiter Sounds indicates that the abundance of this seagrass diminishes in the more turbid interior portion of the lagoon where reduced light limits photosynthesis.

Other areas of concern include seagrass beds located in proximity to rivers and canal mouths where low salinity, highly colored water is discharged. Freshwater discharge into areas adjacent to seagrass beds may provoke physiological stress upon the plants by reducing the salinity levels. Additionally, colored waters released into these areas reduce the amount of sunlight available for photosynthesis by rapidly attenuating shorter wavelengths of Photosynthetically Active Radiation.

Also, continuing and increasing degradation of water quality due to increased land use and water management threatens the welfare of seagrass communities. Nutrient over-enrichment caused by inorganic and organic nitrogen and phosphorous loading via urban and agricultural land run-off stimulate increased algal growth that may smother Johnson's seagrass, shade rooted vegetation, and diminish the oxygen content of the water. Low oxygen conditions have a demonstrated negative impact on seagrasses and associated communities.[3]

Recovery Plan

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has determined that Johnson's seagrass recovery plans should include the following top priority actions:

- Protect the geographic extremes of the range and genetically unique populations.

- Experimentally determine the mechanism for recruitment of patches (clones), and maximum dispersal distances of vegetative fragments. Use this information to determine the number of self-sustaining populations necessary to ensure their presence throughout the range.

- Establish federal and state interagency coordination during the permit review process (e.g., NMFS, COE, FDEP, SJRWMD, SFWMD, FWC) for projects that may affect H. johnsonii or its habitat so that impacts to the species can be avoided or minimized.

- Improve or maintain water quality and sediment conditions appropriate for continuous vegetative growth and reproduction of natural populations of H. johnsonii throughout its geographic range, addressing point and non-point sources and water quality-based targets (PLRGs and TMDLs). Coordinate these actions with existing programs, including, but not exclusively, the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary and SWIM programs and the Lake Worth Management Plan.

- Assess current federal, state, and local seagrass protection regulations and programs (specifically those addressing human activities on submerged lands and within the boundaries of federally-designated areas) for their level of effectiveness in protecting H. johnsonii and its habitat.[4]

Web Links

- NOAA:Critical Johnsons Seagrass Habitat

- NOAA 2002 Recovery plan for Johnson's seagrass (PDF 110pp 640KB)

References

- ↑ NOAA Johnson's Seagrass, retrieved on 12/25/2019.

- ↑ 1998 Johnson's Seagrass Endangered Species Act Listing Rule (PDF 7pp), retrieved on 12/25/2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 NMFS 2000 Johnson's Seagrass Critical Habitat Federal Register Final Rule, retrieved on 12/25/2019.

- ↑ FINAL RECOVERYPLAN for JOHNSON'S SEAGRASS, retrieved on 12/25/2019