Indian River Lagoon Estuary

The Indian River Lagoon (IRL) National Estuary is the most bio-diverse natural habitat in North America.

About the Indian River Lagoon Estuary

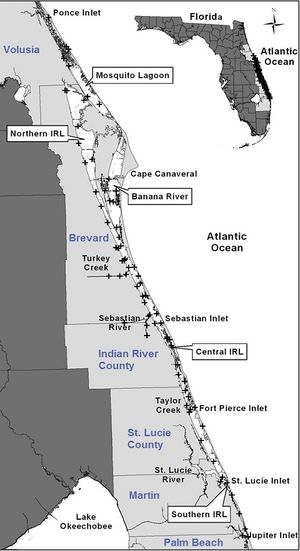

Covering 40% of Florida's East Coast, the 156 mile long[1] Indian River Lagoon (IRL) Estuary merges the freshwater of 5 rivers and the saltwater of 4 ocean inlets into 3 major brackish water lagoons.

From it's northern end at Volusia's Ponce de Leon Inlet, the estuary spans across 6 Florida counties, to meet it's southern boundary at Palm Beach County's Jupiter Inlet. The IRL Estuary contains 5 State Parks, 4 U.S. National Wildlife Refuges, a National Seashore, an Intracoastal Waterway, an Air Force base and a National Space Center.

Because the IRL estuary is located in an area where tropical and temperate climates meet, it's flora and fauna species include the native subtropical and tropical residents, plus many migratory winter visitors. The estuary's saltwater inlets and freshwater tributaries blend together to form the lagoon's brackish water, which provides an unique habitat where aquatic plants and animals from both salt and fresh water, can reside. The Indian River Estuary contains many diverse natural habitats, from sea grass flats and mangrove shorelines to inland forests, that accommodates a vast array of plant and animal species. Home to more than 2,100 plants and 2,200 animals, the Indian River Estuary is the most bio-diverse habitat in North America.[1]

In 1990, the Indian River Lagoon was chosen as an Estuary of National Significance and assigned to the National Estuary Program (NEP) by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Florida's St. Johns Water Management District (SJWMD) was the original local steward, and since 2015 the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program (IRLNEP) has been overseen by a special district of the State of Florida, the IRL Council.[2]

Geography

Averaging only 4' in depth and .5 to 5 miles wide, the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary covers 2,284 square miles with a surface water area of 353 square miles.[1] The Mosquito Lagoon, Banana River, and Indian River are the three main IRL Estuary water bodies. Despite being named rivers, they are lagoons, which do not have a current; their waters only move by wind and a minor tidal flow.

Mosquito Lagoon

The Indian River Lagoon National Estuary's range begins at the northern tip of Mosquito Lagoon, with Volusia County's Ponce De Leon Inlet. Mosquito Lagoon then spans Brevard County, where it connects to the Indian River through Haulover Canal. An outdoor lover's paradise, Mosquito Lagoon is bounded on the west by the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge (NWR), on the east by Playalinda National Seashore, and by Kennedy Space Center on the south.

Banana River

The Banana River lagoon begins at Banana Creek, near Titusville, spans south thru the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), to merge with the Indian River at the southern tip of Merritt Island, Dragon's Point. The middle section of the Banana River lagoon lies in KSC and is closed to all public access. Port Canaveral, at KSC's southern boundary, provides minor saltwater influx when the locks are open. The Canaveral Locks, channel, and barge canal allow sea going vessels to access the Banana River (KSC deliveries), or take the channel westward across the river, transverse Merritt Island's Barge Canal, and access the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) in the Indian River.

Indian River

From it's northern boundary in Brevard's Scottsmoor, the 121 mile long Indian River extends southward thru five Florida counties. Along the way, the river connects with the Atlantic Ocean at Sebastian, St. Lucie, Fort Pierce, and Jupiter inlets. It recieves fresh water from the Eau Gallie, Sebastian, St. Lucie, and Loxahatchee rivers, plus many small feeder creeks. Lake Okeechobee connects to the Indian River in St. Lucie county, via the Okeechobee Waterway and the St. Lucie River. The offical southern boundary of the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary is at Martin County's Sewall's Point, where it meets Palm Beach County's Jupiter Inlet.

Biota

Habitat

The estuary's tributaries, spoil islands, salt marshes, sea grass flats, oyster bars, mangroves, shorelines, and inland forests provide diverse natural habitats for both aquatic and terrestrial plants and animals.

Aquatic creatures such as alligator, turtle, dolphin, manatee, fresh and saltwater fish reside in the shallow brackish water. In the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, a world class birding destination, many types of shorebirds, waterfowl and wading birds, like the roseate spoonbill, are found feeding on shrimp, crustaceans and mollusks near the shorelines. Inland birds of prey including hawks and eagles feed on inland reptiles and rodents or visit the lagoon to feast on it's many fish species. Residing higher up in the palmetto and pine trees the terrestrial animals include wild boar, panther, bobcat, deer, bobcat, raccoons, opossum, armadillo and gopher turtles.

Flora

Seagrass is a critical component to the overall health of the lagoon. By 1990, it had surpassed levels reached in 1943. The lagoon also contains night-blooming cereus.

Fauna

The lagoon contains 35 species listed as threatened or endangered — more than any other estuary in North America.[1] The lagoon has about 3,500 resident species of plants and animals.[3] It serves as a spawning and nursery ground for different species of oceanic and lagoon fish and shellfish. Nearly 1/3 of the nation's manatee population lives here or migrates through the Lagoon seasonally. Red Drum, Spotted sea trout, Common snook, and Tarpon are the main gamefish in the Titusville area of the lagoon system. Between 200 and 800 Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) also live in the Indian River Lagoon.[4]

Nine-banded armadillos comprise one of the 34 mammals in the area. It is a 1920s immigrant from the Southwestern United States. Avians include the American kestrel, Reddish egret and the Roseate spoonbill. Butterflies include the Polydamas swallowtail.

Indian River Lagoon is abundant with bioluminescent dinoflagellates in the summer and ctenophore in the winter.

History

During glacial periods, the ocean receded. The area that is now the lagoon was grassland, 30 miles from the beach. When the glacier melted, the sea rose. The lagoon remained as captured water.[5]

The indigenous people who lived along the lagoon thrived on its fish and shellfish. This was determined by analyzing the middens they left behind, piled with refuse from clams, oysters, and mussels.[5]

The Indian River Lagoon was originally known on early Spanish maps as the Rio de Ais, after the Ais Indian tribe, who lived along the east coast of Florida. An expedition in 1605 by Alvero Mexia resulted in the mapping of most of the lagoon. Original place names on the map included Los Mosquitos (the Mosquito Lagoon and the Halifax River), Haulover (current Haulover Canal area), Ulumay Lagoon (Banana River) Rio d' Ais (North Indian River), and Pentoya Lagoon (Indian River Melbourne to Ft. Pierce)

Early European settlers drained the swamps to raise pineapples and citrus. They dug canals discharging fresh water into the lagoon, five times the historical volume.[5]

Prior to the arrival of the railroad, the river was an essential transportation link.

In 1896 and 1902, there were fish kills in the lagoon from gas from the muck below.

The advent of the automobile, starting in the 1930s, resulted in causeways which diverted the sluggish flow of the waterway. Huge population influx resulted in sewage, and stormwater runoff from roadways, polluting the lagoon.[5]

From 1989 to 2013, the population along the lagoon increased 50% to 1.6 million people.

River modifications

In 1916, the St. Lucie Canal (C-44) diverts excess nutrient-rich water from Lake Okeechobee into the South Lagoon. While this helps prevent life-threatening flooding in the Okeechobee area, it creates toxic blooms after entering the Lagoon, a threat to flora, fauna, and humans. This situation is proving difficult to address in the 21st century.[5]

From 1913 to 2013, activity by humans has increased the watershed for the lagoon from 572000 to 1400000 acres increasing runoff of freshwater and nutrients from farms. Both have been detrimental to lagoon health. The wetlands are needed to cleanse the lagoon. About 40000 acres of land were lost to mosquito control and have been restored, but by 2013, recovery was incomplete.

Mangroves help prevent shore erosion and provide critical habitat for marine life. Between the 1940s and 2013, 85% of them had been removed for housing development.

In 1990, the Florida Legislature passed the Indian River Lagoon Act, requiring most sewer plants to stop discharging into the lagoon by 1996. Some sports fish rebounded in population in the 1990s when gill nets were banned and pollution in the lagoon was reduced. In 1995 the seagrass covered over 100000 acres.[6]

In 2007, concerns were raised about the future of the lagoon system, especially in the southern half where frequent freshwater discharges seriously threatened water quality, decreasing the salinity needed by many fish species, and have contributed to large algae blooms promoted by water saturated with plant fertilizers. In the mid 1990s, the lagoon has been the subject of research on light penetration for photosynthesis in submerged aquatic vegetation.[7]

In 2010, 3300000 lbs of nitrogen and 475000 lbs of phosphorus entered the lagoon.

In 2011, a superbloom of phytoplankton resulted in the loss of 32000 acres of lagoon seagrass. In 2012, a brown tide bloom fouled the northern lagoon. The county has approval for funds to investigate these unusual blooms to see if they can be prevented.

Catches of blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) dropped unevenly from 4265063 lb in 1987 to 389,795 lb in 2012, but with high catches in 1998, 1991, alternating with low catch years. These crabs require 2% salt content in the water to survive. A drought increases the salt content and heavy rainfall decreases it. Both of these conditions have recurred over the past decades and are believed to have had an adverse effect on the crab population.[8]

In 2013, algae blooms and loss of sea grass destroyed all gains.

In 2013, four major problems with lagoon water quality were identified. 1) Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from runoff from the application of fertilizer; 2) an estimated 8 to 11% septic tank failures of tens of thousands of septic tanks in the county. 3) Muck from construction, farming, erosion and dead plants find their way to the bottom of the lagoon, preventing growth and consuming vital oxygen essential to marine flora and fauna; 4) Invasive species, including the Asian green mussel, South American charru mussel, and the Australian spotted jellyfish (Phyllorhiza punctata), eat clams and fish larvae.

In 2016, there were an estimated 300,000 septic tanks in the five-county area bordering the Lagoon.

At one time, sewer plants were worse polluters. In 1986, there were 46 sewer plants along the 156 mile lagoon. They discharged about 55000000 gallons daily into the estuary. The state ended most sewer plant pollution by 1995.

In 2018, lagoon health is better near ocean inlets. Pollution is worse in areas near no inlets, such as the Mosquito Lagoon, North IRL, and the Banana River.[5]

Economy

According to the Florida Oceanographic Society, nearly 1 million people live and work in the Indian River Lagoon region. The Lagoon accounts for $300 million in fisheries revenues, includes a $2.1 billion citrus industry, and generates more than $300 million in boat and marine sales annually.

In 2007, visitors spent an estimated 3.2 million person-days in recreation on the lagoon.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 An Introduction to a Natural Treasure

- ↑ Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program

- ↑ Indian River Lagoon Species Inventory Data Base from Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce

- ↑ BOTTLENOSE DOLPHIN Indian River Lagoon Estuarine System Stock

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 A History of the Lagoon

- ↑ Seagrass biodiversity in the Indian River Lagoon

- ↑ Continuous Monitoring of Underwater Light in Indian River Lagoon: Comparison of Cosine and Spherical Sensors. 1997

- ↑ Lagoon crab catches dwindle (2013)

Web Links

- NOAA Estuary Education Kit

- Indian River Lagoon Watershead from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection

- From the Water: Healing our Lagoon: a 2015 series of Florida Today articles.